House Sparrows Weather Winter in Urban Hollows

The house sparrow in New York City is so common as to be almost invisible, even in winter when migrating birds depart for the season, and it remains to find warmth below dormant window air conditioners and in the crannies of urban architecture. In winter, the house sparrows tend to move together in flocks, drinking from puddles that form on manhole covers and foraging on what food they can find.

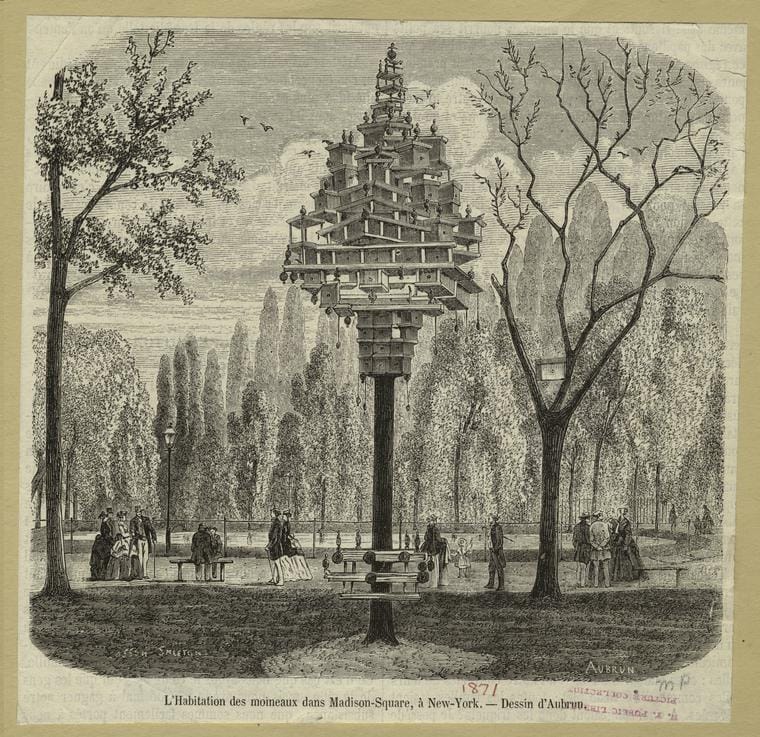

The small, brown, black, gray, and white birds—Passer domesticus—easily blend into street tree branches, building facade bricks, roof eaves, the corners of window sills, and untended tree beds where they take dust baths. Much like the people who built this environment, they were not always here. Their introduction to the United States can be traced back to the mid-19th century, when they were identified as a solution to insect infestations, especially the inchworm that was destroying trees. In the 1850s, after an initial release of house sparrow pairs perished, another 100 were collected in England by naturalist Nicholas Pike. Many of these were released in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery. It was a time of acclimatization societies that attempted to improve on nature by introducing new fauna across the globe, but more often than not, they unbalanced the local environment. In this case, the sparrows flourished to almost alarming numbers. Representatives from New York City’s burgeoning bird population were exported or flew to other cities. They feasted on insects; they also foraged the horse oats that fell out of feed bags on the streets. They survived in the heat and the cold.

But as the house sparrow populations grew, the backlash came, whether from accusations of pushing out native birds to annoyance at the chirping and chattering racket a whole group of the small birds can make. By 1916, the League of American Sportsmen in the Bronx, as reported by the New York Times, had “declared a war of extermination on the English sparrow.” The population did take a hit, but not from armed sparrow vigilantes. Instead, it was the introduction of the car and thus the decline of horse-drawn transportation as a source of oats that curtailed their numbers. Still, they have a global population now estimated at 740 million.

Even on the coldest days, you can usually see or hear the house sparrows, the males with their black bibs and black streaks, the females with lighter brown and white colors, hopping around to forage on the ground or nestling in the small spaces of the city, which we rarely take the time to notice. They stay here year-round because we have, unintentionally, built a perfect home for them to live alongside us. Architectural ornaments designed to beautify the city offer just enough space for a sparrow with its puffy winter plumage to press itself close for warmth and protection; pizza crusts and takeout remnants are a winter feast (if they can beat the starlings and pigeons to them). They may start nesting in February, but for now, they are simply trying to make it through and endure whatever winter will bring.

- Spend time watching house sparrows, and you will see they are not just a riotous crowd of feathers but an organized group with a clear hierarchy. The male with the biggest patch of black feathers on his chest is usually the top tiny bird. But why? As Nicholas Lund writes at Audubon Magazine, “Scientists are still trying to figure that out. The size of the patch doesn’t seem to be directly tied to testosterone level, which often drives similar ornamentations in other species ... What we do know is that badge size does correlate closely with fighting ability, and it also correlates pretty well with age.” So step back and keep an eye out for house sparrow brawls.

- More studies of the house sparrow are underway, as although they are ubiquitous, they have been frequently overlooked in scientific and conservation research. In 2023, the Wild Animal Initiative launched a field research project on the welfare of the house sparrow, with the hope that “a species that is typically ignored at best, and despised at worst — will be understood and valued as individuals.”

- When passing through the Jay Street-MetroTech Station in Brooklyn, take a moment to view Ben Snead’s “Departures and Arrivals” (2009) mosaic and tile mural. The house sparrow is part of a montage of animals recognizing the constant change of local nature, also including non-native species like the European starling and green monk parrot. Installed in a transit station, it recalls how we are all just passing through.